On Sunday night, a friend accepted the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge and nominated Ezra Tischler, this website’s co-founder, to carry the torch. On Monday night, Ezra did so in his own way, writing a thoughtful Blogcat to discuss both his reservations about the ubiquitous awareness campaign and his efforts to spread awareness of the terrible disease in a different manner. I agree with some of his points, and sympathize with others. In general, though, as Ezra said himself when he counteredmy stance on March Madness: “I’ve got to disagree.”

A quote from the well written essay: “I rest firmly in the camp that believes posting a half-minute video on Facebook of me getting doused with ice water will do little to raise meaningful awareness for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), aka Lou Gehrig’s disease.” You can go read his entire, more nuanced take by viewing the source Blogcat, but that quote does a decent job recapping Ezra’s position on the whole matter.

A quote from the well written essay: “I rest firmly in the camp that believes posting a half-minute video on Facebook of me getting doused with ice water will do little to raise meaningful awareness for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), aka Lou Gehrig’s disease.” You can go read his entire, more nuanced take by viewing the source Blogcat, but that quote does a decent job recapping Ezra’s position on the whole matter.

My stance is on the opposite end of the spectrum. As videos started popping up on my wall, and it quickly became pretty apparent that this thing was sweeping the nation, I made a comment that this Ice Bucket campaign was truly genius. Even after reading Ezra’s post, I rest firmly in that camp. This thing is brilliant.

Ezra’s point is that these baseline awareness metrics aren’t that valuable over time. After all, being simply aware that ALS exists in the moment – the type of awareness the campaign succeeds in creating – doesn’t mean that you really understand anything about it or will consider it moving forward. None of these ice bucket videos, including the one that I contributed, have almost anything to do with even surface details of the disease; they don’t describe symptoms, or really make any sort of case for why doing any of this is valuable. The point is, they are simply keeping the ball rolling, but not in a very meaningful way.

Ezra asks us to not be satisfied with merely knowing that this illness exists; to be truly responsible, we should try to more fully comprehend and increase our understanding of it. Read about the different symptoms. Discover the actual advancements researchers are making in fighting the disease. Learn more about the saga of Pete Frates and his battle against ALS that started this whole phenomenon. Maybe in doing all this, we will achieve lasting awareness that will help eradicate it over time. I agree with all this; purely relying on a 2-week stream of shallow videos won’t permanently cement ALS as a top-of-mind issue.

So I agree that taking Ezra’s attitude will result in more meaningful awareness. I didn’t reflect on it before, but it is sort of a shame that the campaign hasn’t done a great deal to teach us about the disease. What I don’t agree with, though, is the conclusion that the typical result – the level of awareness that Ezra finds irresponsible – does not have any merit. Ezra’s attitude is probably better, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the masses’ approach is wrong. It’s a slight distinction, but the nuance is important. We should not feel, as Ezra says, that the whole thing is “tragically ironic” or “wholly irresponsible.”

When my girlfriend nominated me for the challenge, I was in that “wholly irresponsible” segment. Given my high estimation of the whole thing, I’d previously investigated its origins, but I didn’t do anything that Ezra had suggested about learning more. I merely dumped ice on my head, donated $39.50, and nominated three new people that I thought would be inconvenienced by doing the whole thing. I’m an a-hole like that.

Let’s imagine that instead I had done everything that Ezra had said – that I learned a ton of information and pledged myself to donating what I could across multiple years. Better, right?

Well, simply because that situation’s better, does that mean my original surface-level research, and my initial donation, were not meaningful? What’s the qualification? It’s a matter of degree, not of definition, so it’s basically impossible to say.

Regardless, I think a lot of people will still agree with the sentiment that making these videos doesn’t constitute any real contribution, and I think the problem stems from the perfectly sympathetic, but also misguided, emotions referenced in the Slate article that Ezra cited – and to which I refuse to provide the link here. The column discusses the understandable feelings that question what this campaign is really all about: “watch the videos… and you’ll see the stunt was really just about getting their friends to film themselves doing something dumb for no reason. The charity part was an afterthought.”

At the end, the article provides a “more responsible” call to action:

- Do not fetch a bucket, fill it with ice, or dump it on your head.

- Do not film yourself or post anything on social media.

- Just donate the damn money, whether to the ALS Association or to some other charity of your choice. And if it’s an organization you really believe in, feel free to politely encourage your friends and family to do the same.

This whole article, oozing with mightier-than-thou cynicism, makes me so mad.

I get the feelings behind its argument. It does feel like a lot of the people participating in the challenge don’t really give a shit about ALS; because of hardcore narcissism and FOMO, they simply want to get on camera on social media, do something goofy, and then make their friends do it. It would be much more honorable, the thinking goes, to have a more philanthropic motivation for doing this whole thing.

Well, that’s all well and good, but let us not forget the real difference between motivation and outcome. Just because you don’t have the most altruistic intention doesn’t mean that you’re not effecting some good in the world. Do people resent Wells Fargo and the rest of America’s 10 Most Generous Companies for all the money they give to charity, even if they’re simply making donations for PR reasons?

Consider the people who made no donations – what I’m assuming is the majority of participants that are out there. Didn’t they bring at least a small amount of value simply by keeping things moving? I mean, I’m sure in my ice-bucket “family tree,” you wouldn’t have to go too far back in time to find someone who didn’t donate any money to charity, or spend time researching to grow his/her level of “meaningful awareness.” Yet didn’t that continuation of the chain lead, if you think about it, to me donating my $39.50. I totally get feeling dismayed by people thinking they’ve done more to help the cause than they actually have, but that doesn’t mean that they haven’t actually provided value.

Certainly they could have done more, but so could all of us. How much effort is enough? And do we have to be solemn and sanctimonious when we put that effort in?

So what the Slate article calls for – the “no-ice-bucket challenge” – seems to me to be the thing wholly irresponsible. I mean, imagine how this must have all worked. Pete Frates dumped ice on himself, and nominated three more people. They then nominated three more themselves. What would have happened if those 9 people, fearing that they’d be viewed as classlessly following a fad, decided to not dump ice on themselves, but simply donate to charity, and go petition to three more friends? They certainly would have raised some money, and maybe some would have succeeded in spreading the cause, but the chain wouldn’t have caught on in the same way. It just wouldn’t. That’s the typical channel to market for almost every charity, and none of those campaigns are seeing the spike in donations that this one is.

It’s great to wish people had better intentions, and that charities could be more effective by relying on heart-to-hearts by those who campaign for their causes. But that’s not the case. Charities try that route all the time, and basically none have had the results that this one has. I mean, check out the classic Sarah McClachlan Animal Cruelty commercials. What are these heartfelt messages more likely to make you do: donate to save the lives of animals? or change the channel? Better intentions don’t always motivate people to produce better results.

And speaking of motivations: FOMO? Narcicissm? Social obligations? These are real motivations for people! Can we stop for a minute and realize how fucking smart it was for a charity to use social media to leverage these drivers of our behavior? Genius.

Basically, the point here is sort of a practical one. Again, I can see how this whole “awareness” thing can be construed as slightly odd, given the fact that the majority of us haven’t learned all that much more about it, but it’s certainly not “tragically ironic.” I’m sure they could have tried for something with additional substance. In fact, I’m guessing they have. The problem is, we’re not talking about those campaigns. With this one, at least we are.

The campaign doesn’t do everything. It’s true. It’s not a textbook about ALS, and it might not make everybody reflect on the disease 5 years from now. But it did do something that knowledge, sustained over time, cannot do: raise a boatload of money for making an immediate impact on our ability to find a cure. That’s the goal, right? So let’s appreciate it for what it is, instead of deriding it for what it’s not.

So when all is said and done, here’s what I would recommend: Don’t follow Ezra’s post to the extreme pole, but don’t follow mine to the other end of the spectrum either. Definitely don’t listen to that Slate article. Take it all into account, and find that happy medium. Encourage people, and yourself, to capitalize on the opportunity to deepen their knowledge of ALS, but don’t look down on those who do not. All the participants bring value. It may only be a little, but collectively, they all add up to something meaningful.

And remember. As Bill Russell says in the Uncle Drew commercials:

And remember. As Bill Russell says in the Uncle Drew commercials:

“This game has always been – and will always be – about buckets.”

Great Blogcat, I especially like the Bill Russell inclusion.

Your defense is strong and on point, but allow me to throwback a defense of my original Blogcat.

It was not my intention to “look down on” anyone. Due to the popularity of the Ice Bucket Challenge I anticipated I would endure some reactions similar to the one you have toward the Slate article I cited (for the record I do not agree with the entire sentiment of the Slate article. This is something I could have clarified in my Blogcat). For this reason I tried to keep my language and emotions in check while still writing a subjective article.

The point of my Blogcat was, as you also recommend, to “encourage people,” and myself, “to capitalize on the opportunity to deepen their knowledge of ALS.” I even say that, “I urge anyone and everyone to read up on ALS. Become more aware and make your educated decision on how to best help raise awareness.” As you point out, and demonstrated by posting a video, you believe that the best way to raise awareness is by continuing with the video challenges.

I’m not anti-Ice Bucket Challenges, though that may seem hard to believe after reading my Blogcat. I’ve seen plenty of videos in which the participants make note of how people can donate and where they can learn more about ALS. I like these videos. I’m upset by the fact that FOMO, narcissism, and the fear of social shaming is what drives the spread of the video challenges, rather than an actual desire to spread awareness.

As you say, “it’s great to wish people had better intentions, and that charities could be more effective by relying on heart-to-hearts by those who campaign for their causes. But that’s not the case.” You are correct, but can’t we try to make that the case? I realize I’m being an idealist. I note that it is uncomfortable to realize we are unaware. I agree that all the participants bring value, had it not been for the Ice Bucket Challenge I never would’ve done my own research or written my Blogcat. My point is that we can increase that value, even just a little.

I couldn’t really figure out how to work this aside into my post, but I have a in-hind-sight suggestion that drives at some of the desires Ezra and I expressed:

Keep the Ice Bucket Challenge exactly the same, but to spread actual knowledge, before you dump ice on yourself, you have to state one thing that you learned about ALS. This would result in people learning at least a little bit more, not because they would learn things that their friends said, but maybe also because they would be more likely to try and find something new to share that they hadn’t heard anywhere else.

That suggestion still won’t solve the thing that’s rightfully eating at you, Ez – the fact that people ARE far more consistently, and size-ably, motivated by FOMO, narcissism, and social shaming than any sense of genuine altruism.

That fact is a shame. Not sure what we can do about that one, though. Anybody got any suggestions?

Good read, kam bam. I sincerely doubt that this would be an issue in Cleveland 2, but alas such idealistic views are far from present reality. Allow me to delve into absurdity at the risk of making a point.

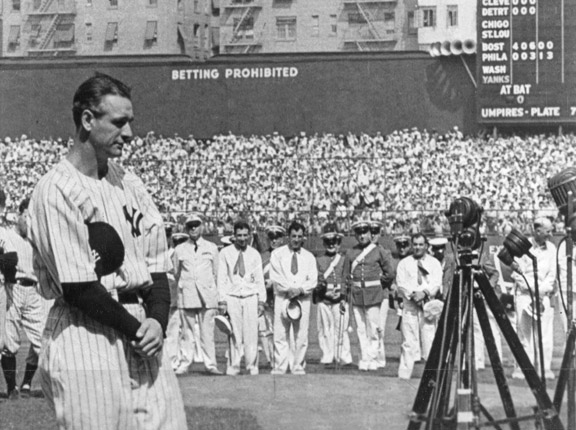

Lou “The Disease” Gehrig once considered himself to be the luckiest man on the face of the Earth: a very powerful statement from a celebrated baseball legend despite the fact that he played for a half rate team. According to the ALS association website, this disease affects approximately 2 in 100,000 people. That’s roughly a 0.002395% chance of getting the disease which is no doubt why Lou considered himself to be so lucky. Based on my calculations [n!/(n-x)!*(t-x)!/t!] you’re more than one hundred times more likely to flop four of a kind in a standard (non-Rexford) hold ‘em game.

My main point being that I wasted too much time trying to remember how to do probability and I’m still not sure if the numbers are correct. My secondary point being that it’s a very rare disease. A third point might be that the ALS challenge did increase my awareness of the disease enough to do a small amount of research. This research, however, led me to the conclusion that there are probably bigger fish to fry. Of course it’s not a bad cause, but it seems that the millions of dollars raised could go a lot further for other philanthropic adventures, e.g. getting the Sarah Maclachlan commercials off the air or funding Primer 2.

I agree with you that the ice bucket challenge has proved to be a brilliant and wildly successful campaign for raising donations to support a good cause. Why not exploit social media? An inevitability of this is that this will lead to many imitators for other causes with equally good intentions, but as the fad burns itself out so will the effectiveness of such campaigns in the future. (See the “Scauses” episode of South Park.) I think soon ice bucket challenges will be as ignorable and arguably ineffective as the “sad pictures of (insert cause) and send us money” commercials currently are.

As my boy Thoreau once said, “Most men used to lead lives of quiet desperation, but nowadays everyone just tweets about it.” He continued, “And as my boy G.W. once said ‘fuck the police.’” I tend to agree with Thoreau on both points, and I’m personally not a big fan of social media in its various forms (or the police). In this light, I think most of the push back is more directed toward the frustrations that Henry David and I feel towards people broadcasting their opinions and the mundane details of their lives online.

To summarize, I read a blog(drogba?)cat online expressing the opinions of its author and responded online expressing my own opinions about how I don’t care about reading other people’s opinions online. I also wasted a lot of time making an excel spreadsheet to calculate poker odds.

P.S. I don’t know how the website gets linked to, but you should totally click on it.

I like to share understanding that will I have accumulated with the calendar year to help

improve team functionality.