I don’t quite remember the year; the poignancy of the memory overpowers any sense I have of my exact age, or even grade, at the time. I was driving my parents’ Volvo down 114 towards Newport. My two closest friends, Spike and David, were in the car with me. David had just put in a CD of some band he was getting into that I had never heard of, with the perplexing name Cock Sparrer. We made our predictable jokes about the name as he switched through the tracks until he found the one he wanted us to hear first. At the time, the extent of my music collection consisted of Led Zeppelin or The Who CDs and a handful of mixes made downloading songs on LimeWire (remember that?).

My friends weren’t a whole lot cooler. We spent a good deal of our time playing “Dungeons & Dragons” or Warhammer 40k. I probably had braces and terrible acne (who am I kidding with “probably”?). My AOL e-mail address and IM screen name, back in the glorious old days of dial-up modems, was “ThundreMage” (in my defense, I soon changed it to “Schnitzel21”). The password I used came from a Magic: The Gathering card (I can hear some light bulbs turning on from people who want to hack my e-mail, to whom I say have fun trying all 20,000 possibilities). Still, I was a middle class white kid living in suburbia, going through puberty, and you know what that means. It means that I was angry, confused, lost, entitled; we – meaning me and my friends – felt alienated. We shunned what we saw as the shallowness of mainstream society, but had not yet found the cultural anchor around which we could situate ourselves in a world we did not create and could not control.

And this brought us all down the road to Cock Sparrer. The music was loud and raw, with a repetitive gruff Cockney shouting as vocals (that has a strange twanginess that I can only ever think to describe nonsensically as “tonky”) over a furious rhythm.

The lyrics are almost the definitive expression of the “punk” ethos: class disenfranchisement (“All they want is total power / Climbing on the backs of the working class”), pacifism (“We don’t wanna fight / Because you tell us to”), individualism (“We don’t wanna be a part of no new religion”), anti-authoritarianism, and anti-Nazi imagery (no musical genre is as perennially obsessed with fascism as punk music). At least, it epitomizes the definitive expression of what the punk subculture claims to aspire to and represent.

When most people think of punks, they picture scrawny and pale, cracked-out white kids with nose piercings, green fan mohawks, and leather jackets. They are not wrong. Fashion is, and will remain in perpetuity, a dominating characteristic of any cultural expression; however, punk is unique in its almost maniacal attachment to what seems fringe and taboo. You might be thinking that the piercing and tattoos (and other stereotypical “punk” fashion statements) are now pretty thoroughly accepted into pop culture, and to a certain extent you are right. Hell, there was even a punk cameo in that movie “Horton Hears a Who”!

(Few things punks love more than partying in underground storage facilities. Trust me.)

On a visceral level, though, punks are not truly mainstream. When most people see someone dressed the way I used to dress on the street, that check their wallet and avoid eye contact. There is a reason people still cover up tattoos and hide piercings for job interviews. In movies and television shows, a nose piercing or dyed hair is used as a visual shorthand to circumvent character developing, instantly signifying the individual as being “weird” or “independent” or “trouble-maker”. There is a pretty immediate assumption of some abstract guilt (hell, have you ever called someone a punk in anything but a pejorative context?).

The popular attitude towards punks has been colored (in some cases fairly, in other cases not so much) by its history of controversy and debauchery: from the 1978 murder of Nancy Spungen and Sid Vicious’ heroin overdose not longer thereafter (a series of events brilliantly portrayed in the Academy Award winning film Sid and Nancy), to Iggy Pop rolling in broken glass on stage, to anything involving GG Allin (seriously, if you have a weak heart don’t even Google that crazy son of a bitch). Famous punk songs have publicly called for Ronald Reagan to be assassinated and likened Queen Elizabeth to Stalin. Criminal charges were levied against The Dead Kennedys for “Work 219: Landscape XX,” circulated with copies of their album “Frankenchrist”.

|

It is interesting how relatively slow and inflexible culture can be at times. When you look back at the history of punk, it is notable that not a whole lot has really changed except exposure and scale. The origins of punk are a bit mirky, though its direct roots lay in the youth culture of the 1950s and 1960s, indirectly they can be traced back even further. The concept of a “counter-culture,” the idea of following a particular ideology or aesthetic that is in some way in opposition to mainstream mores, goes back as far as the 1700s, though not in the modern sense. At least in the sense we define the phrase now, “counter-culture” started with the Bohemian movement in Europe and the United States in the late 19th century. Bohemianism was a lifestyle commonly associated with artistic expression, liberal ideals, and some form of poverty or social marginalization (sound familiar, hipsters?). However, the entire social fabric of the Western world was upended by a series of unfortunate events (Lemony Snicket: please don’t sue) that occurred between 1914 and 1918.

The aftermath of World War I saw the devastation of an entire generation: the war killed 9 million people, and the Spanish influenza that proceeded it killed as many as 50 million. The youth culture of the 1920s and 1930s was profoundly impacted by the stresses of the war: many young kids, as young as 16, had seen service on the front, and the kids too young to serve were often left fatherless and brotherless. The Great Depression only made things worse. Teenagers and young adults who had been thrust into the position of supporting their families by the war were now left unemployed.

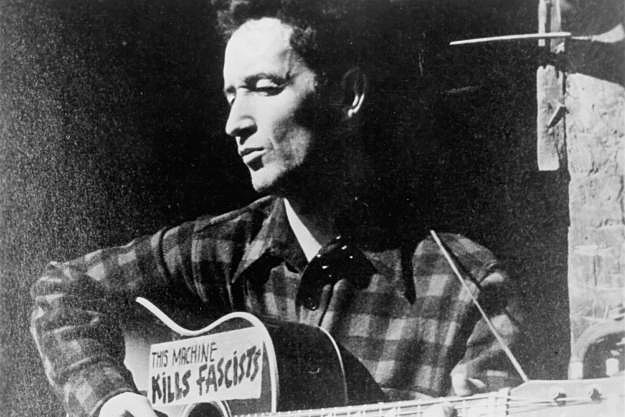

The 1930s saw the Spanish Civil War, which pitted the Nazi-backed fascists (a.k.a. THE movie villains) against the socialists and anarchists. Although radio and newspaper had existed prior to World War I, the prevalence of these media, and their ability to quickly disseminate information across the country, was unprecedented. Disenfranchised youths, hardened by the terrible events of the preceding decades, hitched boats to Europe to go fight in the war. It was the most heavily romanticized conflict since the Charge of the Light Brigade: Ernest Hemingway, George Orwell, and John Dos Passos wrote extensively about their experiences in Spain during the war. Woody Guthrie sang songs about it, sporting a guitar emblazoned with the words, “THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS”. It was very widely viewed as the clash of good and evil, with the poets, the musicians, the artists, and the intellectuals coming down against the malignancies of the fascist war machine.

|

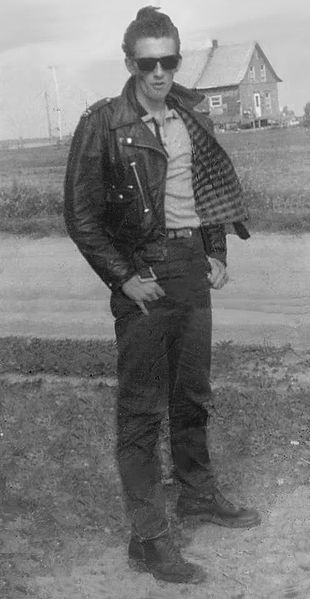

The Spanish Civil War, and World War II, not only acted as an ideological flashpoint, but perpetuated and advanced the cultural shifts initiated by the First World War. The 1950s saw the confluence of emergent revolutionary ideologie with unprecedented economic prosperity and, of course, the Baby Boom. There was suddenly a very large population of youth, inundated by the propaganda and discontents borne out of the world wars, with money and leisure time (not to mention the technological developments that brought music and television more permanently into people’s lives). Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and the Beat generation captured the public imagination with tales of partying, traveling, and living in the margins of society. Across the pond, a band named The Quarrymen made a name for itself playing pubs and rehearsing in an abandoned air-raid shelter; they wore leather jackets, smoked cigarettes, and played the “bad boys” (the band would change their names several time over the years, until 1960 when they finally starting calling themselves The Beatles, and their careers took a different turn).

|

There was nobody more romanticized in the 1950s than the outlaw. Besides the Beatniks and the growing culture of rock and roll, there were the Hell’s Angels and other biker gangs in their leather jackets and studded denim (the 1953 Marlon Brando vehicle “The Wild Ones” turned them into outlaw heroes, a perception that would endure; even today, there is some “Easy Rider”-type association between motorcycles and the cliche “freedom of the open road”). All across the country, kids would become greasers or hoods (in England, the equivalent were the so-called Teddy Boys): listening to rock and roll, to the dismay of their cartoonishly conservative parents, letting their hear down or wearing it up with gel, wearing jeans and t-shirts instead of proper suits and slacks. The post-war boom saw the first real burgeoning of what we now definitively refer to as a youth culture, or subculture (a facet of 1950s America that is conveniently left out of the overly nostalgic view we are used to in TV and movies is that the scourge of methamphetamine and heroin addiction was first gaining prevalence – which everyone blamed on communists, the blacks, and, oddly, the Nazis).

|

Concurrent with the explosive growth of this subculture was the wild backlash from the mainstream, fueled by a mixture of typical “won’t somebody PLEASE think of the children!” conservatism, the obsessive focus on formality and presentation that made the 1950s look so suave and debonair, and irrational McCarthyist terror of anything that looked or felt “leftist.” As I am sure most of you are aware, youth (especially those with a bit of money and a bit of freedom) don’t take kindly to being told what to do, how to act, how to dress, etc. For the first time in the history of disgruntled teenagers, however, there was a definite outlet besides running away or sucking it up. Music, movies, books, poetry, and art were all widely and easily available as external referents and the rise of the middle class (and end of the Great Depression) diminished the burden of necessity. Kids had the time and the ability to socialize more or less at will and the ability to tap into and access a wider range of cultural and creative expressions than had been available before the advent of TV, radio, and modern magazines.

After the 1950s, the history of subculture becomes more familiar. Everyone who is reading this will know something about the hippie movement of the 1960s, the Summer of Love, and the transformation of rock and roll from a fringe pass-time, epitomizing the rejection of the cultural mainstream, to a genre that is now considered literally definitive of the cultural mainstream. The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, The Who: all began as records kids would hide from their parents; now, typically, they are hidden somewhere in your parent’s attic or garage.

As rock and roll became more and more mainstream with the aging of that generation into respectable citizenry, their children, the new disenfranchised youths, had to look to something new to define themselves. Young people will always try to reject cultural definitions handed down to them and look for a unique way to define themselves in a world they are only just beginning to be able to understand on an intellectual and philosophical level: however, people are, by evolutionary prerogative, social creatures. We don’t want to be alone and at some level we don’t want to stand out too much. So youth coalesce around some vague mutually agreed upon set of norms that define a new subculture.

The population of the US (and the world) increased exponentially (there were 2.5 billion people alive in 1950; in 1970 there were 3.7 billion) while technological advances were diminishing the once exorbitant price-tag of studio recording, broadcast, print, etc.. In the same way that independent/art-house movies have become increasingly prominent in the past decade or so, due to the relative ease and low cost with which one can make a movie now (for example, “Primer,” which went on to win the Grand Jury prize at Sundance, was made for only $7,000 in 2004. Also it seriously kicks ass. If you haven’t seen it go watch it right now, preferably without reading anything about the plot/premise first.), the 1960s and 1970s saw an increase in the number of independent publications and record labels. Suddenly, there were more young people with greater access to art and mass media (and their peers) than there ever had been before; it is no surprise, then, that the idea of a singular counter-culture began to fade.

While youth culture has never been an entirely monolithic construct, there was now a structure in its fragmentation. Since more people were able to create and appreciate art, there were now more forms and varieties of art. Largely arbitrary divisions based on abstract instantiations of taste, emotion, or a hundred other factors served as social landmarks by which different subcultures could emerge and define themselves. The late 1960s and 1970s not only saw the hippies, but subcultures like disco, bikers, surfers, skin-heads, mods, black power, and, of course, punk.

So it was, during this time, that the first of what would later be referred to as “garage bands” began to emerge: young people with the time and resources to get instruments, spent time practicing, start playing at local venues, and, eventually, even record their own records. The music was raw and unpolished, almost dripping with angst, with heavy distortion and aggressive, sometimes screaming, vocals. Bands that many of you will probably not recognize unless you’ve researched this subject before: The Standells, The Sonics, The Seeds, Troggs, The Leaves, Paul Revere and the Raiders (whose single “Kicks” was number 4 on the US charts and is included on Rolling Stone’s list of the 500 greatest songs of all time), and Question Mark & the Mysterians. 1971 saw the first published use of “punk” in a music review, referring to the last of these.

It might seem odd to call that a “punk” song from a “punk” band. And if you listen to some of their other hits (i.e. their songs that have lasted long enough for somebody to turn into a YouTube video), like “96 Tears” or “Ten O’Clock”, it seems even more ridiculous. But then again, the phrase “heavy metal”, which causes most people now to think of this:

Was originally used to refer to this:

You can probably hear some parallels between the contemporary definition of the genre and its antecedents, but for the most part they seem like different styles. In any case, the seeds of punk had been planted from a musical stand-point. However, it took the economic downturns of the late 1970s to transform punk again, especially across the pond in England. Increasing social and public backlash against liberal ideals (above everything, still, loomed the specter of the Cold War and the fear/hatred of communism), the slow demise of industry and manufacturing, racial tension and the massive violent riots that came along with it (an extraordinarily significant event in American cultural history; the events surrounding them are almost singularly responsible for cities like Newark and Baltimore remaining crime-ridden well into the 21st century), and rising unemployment all bred discontent and alienation within the youth culture. Further, the philosophy of punk was one of open-mindedness and freedom, and as such attracted social outcasts (in fact, especially in the early years but even to some extent today, many punks are artists, homosexuals, transvestites, or other marginalized youth).

This is when bands like Richard Hell and the Voidoids, the New York Dolls, the Sex Pistols, the Ramones, and the Stooges came onto the scene. Driven by social and economic discontent, the lyrics are full of rage: against the government, against the rich, against society. They dressed to shock: excessive piercings, tattoos, radical hair, radical clothing. They hated what society had become and wanted to undermine it:

The Dead Kennedys likened the governor of California to Hitler.

The Clash sang about the heavy-handedness and brutality of the police.

Black Flag told their audience to rise above “society’s arms of control.”

A 1981 documentary about the nascent punk scene was called “The Decline of Western Civilization,” and prompted a letter of complaint from the chief of the Los Angeles Police Department.

The 1980s saw the height of punk as a genre. It grew in popularity to the point that it, like the counter-culture of the 1950s and 1960s, fragmented. Straight-edge, hardcore, skinhead, cowpunk (a mixture of country and punk … which I know sounds strange to many of you, but anyone closely involved with the punk scene has noticed the rather strong philosophical affection punks have for country/folk music), anarcho-punk, psychobilly (don’t ask), skate punk, street punk, oi … subgenres within subgenres, each with their own-distinct sounds and aesthetics. I could write another 3000 word article simply detailing the differences between the different varieties of punk (hell, I could write a 3000 word article on crust punks alone). The 1990s generally saw the regression of punk, in so far as it was no longer a new and revolutionary lifestyle, and the culture has been more or less static ever since.

I first began listening to punk in the early 2000s. The music appealed to me because it was loud, angry, and different. It intrigued me, even if at first I didn’t even like it that much. As time went on, I began to explore the different artists and subgenres that make up punk. There were several mainstream venues in Providence, RI that would host punk bands (AS220, Lupo’s), but for the most part the shows were in old mill buildings in Olneyville, squat-houses, or in apartments. The same venue’s exact location could change from show to show (looking at you REDRUM). Heck, there are venues I visited multiple times but would still have a difficult time locating now, like Darwin House. One of my fondest memories is, after a show headlined by bands with names like Hulk Out and Dropdead, was drinking whiskey and listening to Johnny Cash in a house, which I would only later find out was unoccupied, and we were there illegally (also, if my parents are reading this everything I just wrote was a lie, don’t worry about it).

As I became more involved with the scene and the music, I began to appreciate it more. Punk music is more varied than many give it credit for. From the reggae and hip-hop influenced rock of Bad Brains:

To Iggy and the Stooges, who sound more like The Doors ugly cousin:

To the strange experimentations of the Butthole Surfers:

To the gothic drone of The Misfits:

To the sarcastic anthems of Black Flag:

To this song, which I can’t describe but highly recommend:

And the noise rock of Lightning Bolt:

When I listened to punk, it was either local Rhode Island bands (being, generally, the only ones I could actually see live) or older punk bands from the 1970s and 1980s. I remember it being a point of pride that there was a hidden intellectualism to punk. In a way that would now be described as hipster, there were times where the entire aesthetic and ideology of punk felt sarcastic and ironic. Jello Biafra, the lead singer of the Dead Kennedys, studied acting and South American history at university, and is now a poet and member of the Green Party (he actually was a candidate in the presidential primaries back in 2000). Henry Rollins, of Black Flag, became a respected writer and actor. Greg Graffin, of the band Bad Religion, has a PhD in zoology from Cornell University (and has taught classes in evolution, anthropology, and geology at several major universities across the country). Milo Aukerman of The Descendents, on the other hand, earned his PhD in biochemistry from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

I don’t know exactly when I came to this realization, but eventually I realized the problem with the punk scene: it was not only hypocritical, but it was also a strange form of fantasy fulfillment. When you listen to the lyrics of punk songs, or read punk ‘zines, it is always about freedom, acceptance, and other distinctly liberal ideals. The reason the scene exploded in the 1970s and 1980s was because of its inclusivity: anybody could be a punk, because it was ostensibly more of a philosophy than a distinct culture; it attracted artists and outcasts of all sorts. That is, it is inclusive as long as you dress like a punk, act like a punk, listen to the newest and most hardcore punk bands and not the ones that were perceived as having “sold out”, etc. The problem with humans is that on an instinctual, evolutionary level we crave boundaries between ourselves and a proverbial other; however, humans are too inherently shallow for these boundaries to be anything but the most superficial possible.

Further, just about every punk I ever met was a middle class white kid. While there are exceptions (and historically this was not always the case), you are dealing with a group of well-off youth intentionally ripping their clothing and talking about working class pride. While there is nothing inherently wrong with this, per se, it is still disingenuous. I knew kids who dropped out of high school and started doing heroin, essentially for no justification other than they thought that it was cool. All of the usual problems associated with drug use and unprotected sex are prevalent in the punk community. And for all the music I listened to, all the leather jackets and studded denim vests I wore, I was never a true punk; I went to school, did my homework, still played Dungeons & Dragons (hey, fuck you), didn’t shoot up, didn’t run away and hop a train, etc.

At this point, I haven’t gone to see a punk band live in 4 or 5 years, at this point. I don’t wear my bullet belt anymore. I still occasionally listen to punk music, but for the most part my tastes have evolved beyond that. I had embraced those elements of the punk ethos that I thought were positive: pacifism, individualism, freedom, DIY, etc. The idea that someone could look like a scumbag on the outside while still being intelligent and well-adjusted is one that I still find appealing. Unfortunately, the punk scene is not so much interested in ideological purity as it is in conformity. In the end, it is no less rigid and arbitrary than the mainstream culture that it purports to undermine. As a subculture, it has become bogged down in the most materialistic aspects of its tropes.

On the other hand, that is exactly the risk you take trying to define yourself as being a part of a particular subculture or group. When you are young, you don’t know any better. You are only just beginning to achieve the level of self-awareness necessary to even understand what it means to categorize yourself in this way. And I do not regret or begrudge my past; I think that the time I spent with punks opened my mind to such a variety of new ideas and forms of expression that it has made me a better and more rounded person today (and yes, I realize how corny that just sounded. Shut up, write your own blog). It is because of punk that I went on to explore other genres of music, that I have such a finely ingrained sense of injustice and sympathy for the alienated/dispossessed, that I would rather do something myself than pay someone else to do it for me.

Everyone goes through phases like this. It doesn’t have to be with punk. It is part of our need to situation ourselves within a clearly defined social group. As you get older, such distinctions begin to seem less significant. All you can do is adapt.

|