I’m not exactly sure what made me want to write about Calvin & Hobbes. Talk about a train of thought beginning to a Blogcat!

I’m not exactly sure what made me want to write about Calvin & Hobbes. Talk about a train of thought beginning to a Blogcat!

Ahh, now I remember. Right around the time (mid-August) my girlfriend and I moved into our new apartment, Breaking Bad was at the forefront of my mind, as the final 8 episodes were in the midst of airing. As we were decorating the place, or more specifically the bathroom, I realized it’s often nice to have some reading material when sitting on the throne. Again, the Breaking Bad thing, so I thought it’d be great to leave my copy of Leaves of Grass atop the porcelain backing.

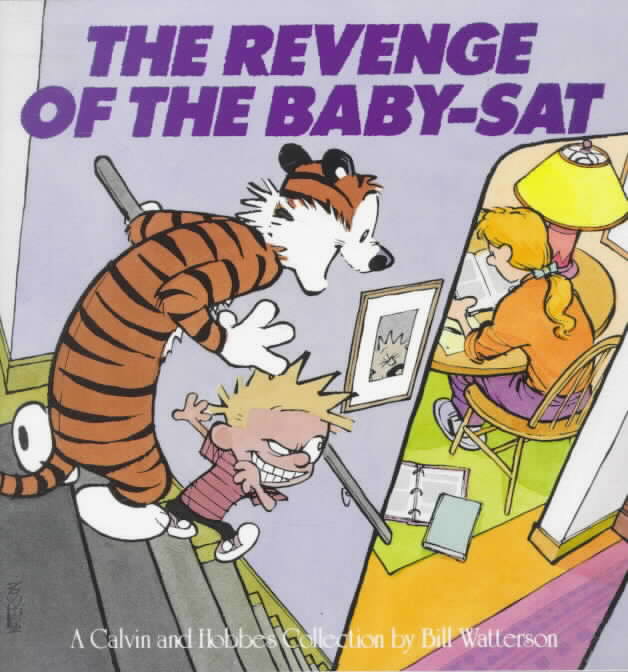

A few weeks later, though, I woke up early for work, went to the bathroom, and realized that, while having some material to sift through would still be nice, navigating the dense and convoluted Song of Myself, though still a fantastic piece of literature, was not exactly what I was looking for when exhausted and bleary-eyed. Afterward, I went to the bookshelf and grabbed something on the opposite end of the spectrum: Revenge of the Babysat. Now every morning in the bathroom, whether I use the toilet or not, I see a masterpiece by both Walt Whitman and Bill Waterson. That daily reminder got me thinking.

Calvin and Hobbes, for those unfamiliar, is a glorious comic strip featuring an impudent six-year-old boy and his stuffed/animated tiger. It’s by far my favorite of all time, and it really doesn’t have a competitor. For summarizing beyond that, feel free to check out the wikipedia. I don’t have the space here to do it justice.

What I can touch on is that, simply put, the comic has played an enormous role in my life. Other than the possible exception of Harry Potter (though I doubt it), there was nothing I read and re-read more often. It was basically like a PG version of South Park, with Calvin as Cartman with a different vibe. For an adolescent Josh Kambour, there was nothing better than reading about the misadventures of that witty little spiky-haired smart-ass.

One reason the strip resonated so well was that it was so easy to put myself in Calvin’s shoes. I was an only child (and I actually had a stuffed tiger at one point, now that I think about it) who was often forced to entertain myself simply using my own imagination. More importantly, though, it touched on situations almost every kid must face: babysitters (Rosalyn), bullies (Moe), teachers (Mrs. Wormwood), made up games (Calvinball), make-shift toys (Transmogrifer), and of course, the push and pull of juvenile flirting (Susie).

One reason the strip resonated so well was that it was so easy to put myself in Calvin’s shoes. I was an only child (and I actually had a stuffed tiger at one point, now that I think about it) who was often forced to entertain myself simply using my own imagination. More importantly, though, it touched on situations almost every kid must face: babysitters (Rosalyn), bullies (Moe), teachers (Mrs. Wormwood), made up games (Calvinball), make-shift toys (Transmogrifer), and of course, the push and pull of juvenile flirting (Susie).

Calvin’s parents played a big part, too. The genius there was that their only names were Mom and Dad. It wasn’t about their story. Sure, they were part of Calvin’s story, but only in their relationship toward him. And really, that’s how we all view life. Obviously the world is the story and we’re all just making cameos, but the subjective nature of reality makes it so narcissistic.

Beyond the similarities in our lives, it was just such a deep piece of art, and that makes it hard to pin down exactly why it was so great. It ran the full spectrum.

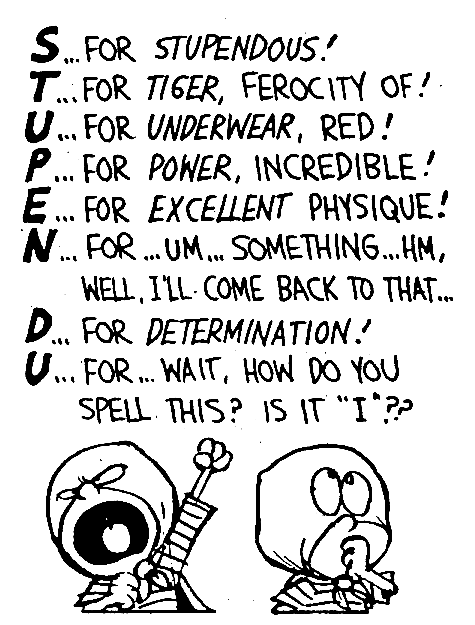

It dabbled in the delusional inanity of the juvenile:

but also humor that plays on adult themes, like parenting and politics:

It touches on age-old questions:

but also comes at you from out of left field:

The graphic design can serve merely as the backdrop for text-based humor:

Or be a visual wonder at the forefront of the comedy (I mean, how funny is the terror on the faces of those snowmen?!):

It can make you happy…

make you crack up out so loud at work that your co-workers notice…

or, of course, tug at your heart strings:

The many faces of Calvin and Hobbes make me just absolutely love the thing – not just every frame, but the world as a whole – because it’s real life. Life is not a comedy, tragedy, horror, or soap opera. It doesn’t fit inside of those specific characterizations. It’s all of those things. I own every Calvin & Hobbes anthology, and have read each of them like 395 times. It never gets old, and that’s sort of what I want to touch on to end this piece.

We see people, mostly celebrities, “sell out” all the time, compromising the moral or aesthetic integrity of themselves or the work they’ve produced in order to make a buck. Ice Cube told us all to Fuck the Police, and now he’s doing Coors Light commercials. The Rock makes Tooth Fairy. George Lucas makes a second Star Wars trilogy, and then his buddy Spielberg teams up with Han Solo to make a fourth, legacy-damaging Indiana Jones.

We see people, mostly celebrities, “sell out” all the time, compromising the moral or aesthetic integrity of themselves or the work they’ve produced in order to make a buck. Ice Cube told us all to Fuck the Police, and now he’s doing Coors Light commercials. The Rock makes Tooth Fairy. George Lucas makes a second Star Wars trilogy, and then his buddy Spielberg teams up with Han Solo to make a fourth, legacy-damaging Indiana Jones.

It doesn’t even have to be motivated by a pure money-grab. Something like Michael Jordan coming out of retirement leaves a bad taste in my mouth, because now there’s proof he was mortal. Arrested Development’s fourth season was fine, but it didn’t match the bliss that came before it (Annyong!). These returns were inspired by a true desire to duplicate what came before, but they ended up diluting our public memory.

Bill Waterson refused to sell out Calvin & Hobbes no matter how many different offers he received. As Wikipedia states, “Watterson [insisted] that cartoon strips should stand on their own as an art form, and has resisted the use of Calvin and Hobbes in merchandising of any sort.” If you think about it, that still holds true today, 23 years after the last frame was published. Sure, you might see some unlicensed car-decal caricature of Calvin peeing, but that’s about it. No T-Shirts or key chains. No TV show or movie. Just the pure, unadulterated brilliance of the comic strip.

It’s hard to believe that he did that. We, the public, hate when celebrities “sell out,” because we have nothing to gain when they do; we don’t see that multi-million dollar paycheck, only the damaging of our collective impression of that beloved something. Furthermore, we like to get on our high horse and preach about how, if we were in that position, we would stand our grade for the sake of the art.

It’s hard to believe that he did that. We, the public, hate when celebrities “sell out,” because we have nothing to gain when they do; we don’t see that multi-million dollar paycheck, only the damaging of our collective impression of that beloved something. Furthermore, we like to get on our high horse and preach about how, if we were in that position, we would stand our grade for the sake of the art.

For the vast majority of us, though, it’s a complete fallacy. Adam Carolla, my favorite podcast host, acknowledges this bluntly; for years, he referred to Mountain Dew as “Nectar of the ‘Tards,” and joked that anyone who drinks it in high volume is destined for junior college. Yet, when the company came a-callin’ to do a radio ad, Carolla was happy to oblige. He will readily admit all of this. And wouldn’t we all do the same?

That’s why, though, it’s such a nice change of pace to see Waterson protect what fans of the strip hold dear. He allowed us to maintain that cherished image. As Waterson explains, “I wasn’t against all merchandising when I started the strip, but each product I considered seemed to violate the spirit of the strip, contradict its message, and take me away from the work I loved.” And as you read the following two strips, it’s not that surprising:

I’m sure Bill Waterson became very wealthy off Calvin and his stuff tiger, even after turning down those deals; after all, his creation was one of the most successful comic strips of all time (his 18 anthologies have collectively sold over 45 million copies!). Yet he was definitely turning down a lottt of money; he was passing up, as Bill Simmons would say, getting to that “Eff-You” level of money. You can’t really blame anyone who’d take that route, either. Fans, like me, probably would have wanted him to. That’s how we end up with Anchorman 2. I mean, I salivate at the idea of a Calvin & Hobes cartoon show. Yet it would never be the same.

Bill Waterson didn’t take the money. He held out, for Calvin, and for Hobbes. For Stupendous Man, Tracer Bullet, and Spaceman Spiff. He held out for all of us. And I’m thankful that he did that.