Apologies again to all non-frat readers; these next blogcats are going to concentrate heavily (i.e., entirely) on pong. Also, yes, I’m aware I take this way too seriously.

Never played pong before? Or just played a bit, and it’s been awhile? Well, if you want to get scrubbed in on the rules so you can follow what’s going on in my previous, this, and my next Blogcat to try and make sense of everything I’m talking about, then check out the official DKE Pong Rules & Regulations Guide I put together in a separate post. After that, do yourself a favor and go play.

Now, to the more advanced stuff.

A few weekends ago, our friend Nog hosted a post-Memorial Day party, much of which focused on a pong tournament. 9 teams were in attendance, only 1 of which was not rostered entirely by brothers of my fraternity – DKE Rhos. The competition was structured in 3 groups of 3 teams, with each team playing the other two teams in its group. The winner of each group advanced to the playoffs; out of the three runners up, the two with the best point differential competed in a play-in game to qualify as the 4th play-off team. Single elimination playoffs ensued, ultimately crowning one champion. This year, the hosts took home the belt.

Congrats Nog and RJL. We’ll get you next year.

Ever since Brother Pi, the first official Pong tournament (tournaments played across the 4 hours of ritual hours, with games to 11, don’t count), we students of the game have been tracking gameplay statistics. Our initial data collection was very rudimentary – we only tracked hits, saves, sinks, and wins. It’s certainly understandable, given it was our first stab at it, but it’s frustrating in hind sight because we left so much information on the table (pun intended). The graduating class under me did a more thorough job the next year during the “DKE Open” or “Cabbage Cup,” adding in stats for Save Opportunities and Unforced Errors (UFEs), but there was still a wealth of information yet to be captured.

After ruing our lapse in diligence for years now, this spring’s NogFest gave us the perfect opportunity to redeem ourselves, and track so much data we could apply to the Sloan Conference. We set up a video camera using my laptop, and recorded every single rally of every single one of the 13 games of the tournament (alright, so we missed three in a single game, calm down). The resulting data set is massive; honestly, it’s pretty freaking sweet.

Certainly, we can look at some of our old favorites, like Sinks Per Game, but there are so many others that we can now examine. We can calculate Save %, UFE rates, Serving %, and the granddaddy of them all – Shooting Percentage. We can look at tournament wide averages to evaluate player performance across the entire competition, or drill down on specific games to understand, for example, which player had the best single-game defensive performance.

I’m working on a separate Blogcat that will dive into all these stats, and many more. But almost all of those, while fascinating to me, are purely about evaluating player performance. In this light, Bullets has already mentioned trying to develop one ultimate number to grade how well each player played, and that’ll be super interesting too. What I want to propose in the meantime, though, doesn’t have anything to do with ranking players, or measuring what numbers they individually put up. Instead, after looking at certain numbers from this tournament, I’m, proposing a theory that, though focused on a relatively minor part of the game, represents a radical departure from traditional in-game tactics.

What I am arguing is simple: Don’t Doobie.

For ease of reference, I’ve taken a passage from the Pong Rules & Regulations Guide:

“Regulation pong tables are edged with a thin metal trim, referred to as the “Doobie Rack.” If the ball strikes the Doobie Rack, this triggers the possibility of resetting the point… This does not, however, necessitate the resetting of the point; instead, whether or not the point is (a) reset or (b) continued is up to the discretion of the team who is playing on the side on which the Doobie occurs.”

For as long as I’ve been involved with pong, it has universally been accepted that if it is your own serve, you should catch the ball to reset the point; if it is your opponents’ serve, you should try to continue the rally.

Everybody got that?

This tactic is built on the belief that having the serve is an advantage. At the very least, it would seem to garner you another shot attempt, so your odds increase from a pure volume standpoint, but it also seems we’ve all believed that serves are more dangerous than shots during live play. This is why, on the other end, you want to continue the rally during your opponent’s serve if at all possible; you do not want to give you opponent an extra one.

This tactic is built on the belief that having the serve is an advantage. At the very least, it would seem to garner you another shot attempt, so your odds increase from a pure volume standpoint, but it also seems we’ve all believed that serves are more dangerous than shots during live play. This is why, on the other end, you want to continue the rally during your opponent’s serve if at all possible; you do not want to give you opponent an extra one.

Before, this generally accepted idea – that Serving is an advantage – has been built on purely anecdotal experience, and the disheartening feeling which is getting sunk against on the serve. There’s probably also the perception that you get to take your time, and aim more carefully, and that would result in a more accurate shot. However, because of the video tracking we set up for NogFest, we’ve been able to put some raw numbers behind this assumption.

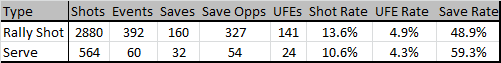

Here’s the breakdown of every shot taken in the tournament:

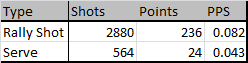

Basically, the average normal shot is more likely than a serve to contact or go into the cup. It’s also less likely to be saved, this time by a substantial margin – 10.4%. When you combine the lower shooting percentage with the lower Hit Rate (Hits/Contacted Cups) for serves, you can calculate Points / Shot (PPS) to compare:

That’s bad news for Serves.

The only saving grace for Serves seems to be UFE rate, as you might have picked up on in the first table above; 4.9% of normal shots result in UFEs, whereas only 4.3% of Serves directly lose your team the point.

That might be an advantage for Serves in a vacuum, certainly, but we’re only discussing the specific situation when you’re deciding which Doobie option to choose. In that situation, you have a 0% chance of hitting a UFE, because even if you hit it off the table, it would just get reset and you wouldn’t lose a point. If you were to catch the doobie to give yourself another serve, you would actually be increasing your single-shot UFE probability by 4.3% – about 3 UFEs over the course of the average game.

Now, some of you readers might look at that latest figure and delude yourself into thinking you have more control with your Serve than the average player, and you pride yourself in being careful to never hit it off on the Serve. Yet I’m sure you’re not the only one who feels that way, and you’re all probably wrong. Of the 16 DKEs in the tournament, all but 4 of them (Bullets, Spieler, Brandt, and Paro) had Service UFEs – myself included.

I think this overestimation trap occurs not just with our narcissistic feelings that we personally keep it on the table, but also with our confidence in our Serves in general. In fact, when I first suggested we shouldn’t be catching doobies in an email exchange with Nog, he had this response:

“The doobie strategy, for me, was always completely dependent on who is serving, e.g., if my partner isn’t good, I’m playing as many doobies as I can. If he is good, I’m catching all doobies. For the elite, it’s a rule, for the masses it’s an option.”

I had never thought to be as player-specific as that, and that’s probably a better approach than the blanket one I’d previously assumed, but I still think that’s wrong. The numbers are pretty clear in that, no matter who is serving, Nog should be playing every single doobie he can.

I think this point is easily made looking at Nog in particular, who is truly elite not only in reputation, and because he won his own tourney, but because the numbers bear that out – he lead the 18-player field by a country mile in shooting percentage across the tournament, generating Events (contacting or sinking) at a 22.3% clip (more on stuff like this in my next Blogcat). That’s quite lofty.

You know what’s not quite as lofty, though? Nog’s Serve Percentage, coming in at an even 14.0%. I think that’s actually pretty good (he finished 5th in Serve Rate, but there’s just a much smaller sample size for individual player Serves), but it’s clearly not the reason his overall Shot Rate was so high. That was instead because he dominated during Live Play, shooting a remarkable 24.3% – again, best in the competition.

You know what’s not quite as lofty, though? Nog’s Serve Percentage, coming in at an even 14.0%. I think that’s actually pretty good (he finished 5th in Serve Rate, but there’s just a much smaller sample size for individual player Serves), but it’s clearly not the reason his overall Shot Rate was so high. That was instead because he dominated during Live Play, shooting a remarkable 24.3% – again, best in the competition.

Now, not all doobies are created equal. Certainly the average doobie bounce isn’t as tasty as a normal missed shot, and if Nog has to make a lunging attempt while falling to the side just to make contact with his paddle for an attempt that he can’t aim, he’s probably better off catching the ball and playing his 14.0% Serving odds.

If, on the other hand, he gets a solid bounce and a clean look at the cup, he’d be crazy to not shoot. He’d be 10% less likely to succeed, and – even with his elite 1.9% tournament UFE rate (UFEs/Shots) – infinitely more likely to directly lose his team a point.

Nog is not the only player who’s Serve Rate was worse than his Rally Shot Rate; in fact, the majority of players were like this, and the ones who weren’t are likely relying on a small sample size of serves, in which lowering their Successful Serves count by just 1 or 2 would change that dynamic. So in general, I feel like it’s fair to conclude that, no matter who you are, you’re probably much better off taking the clean, live look than catching it, despite your confidence in your serve.

So why do we think this is? Why are we generally worse at serving? And why are they generally easier to save?

As to the saveability factor, there’s probably a slight advantage gained because players are more likely to be set and prepared; rather than having to step in and out, navigating your partner’s presence, during Live Play, a serve returner can get in a defensive stance and see the shot coming well in advance. That edge is probably marginal though, and not likely to explain the entire 10.4% disparity in Save Rate.

What I think is likely the bigger factor is that the average loft on Serves is much lower than the average loft on a Rally Shot; even though you rarely see egregiously low Serves, you also don’t see truly towering ones either. This lower arc is much easier to save, because the shot is more likely to hit the front of the cup at the lower trajectory; thus, the bounce is more predictable from a practical standpoint, and subsequently easier to save.

In saving, it’s not just your hands and your touch – anticipation is enormously important too so you’re in a good position.

As to the overall worse accuracy of Serving, the influence of the table itself, something Nog pointed out, is probably the biggest variable. When you Serve, you have to strike the ball in a way that it bounces on the table before going over to the other team’s side. Not only does that mean you’re only indirectly aiming at the eventual target cup, but there’s also less predictability because of the added, not perfectly flat surface. Factoring that in, the player has less control in where the ball goes because the ball could bounce weirdly off the table; there are weird dips in the wood on any table, and it’s just hard to know exactly how it will bounce. Even beyond that, though, it’s also just simply another variable, so even if the table’s surface were 100% flat, it would still add something to the list of things you have to perfect, in comparison to the single contact with your paddle made in a Rally Shot.

As to the overall worse accuracy of Serving, the influence of the table itself, something Nog pointed out, is probably the biggest variable. When you Serve, you have to strike the ball in a way that it bounces on the table before going over to the other team’s side. Not only does that mean you’re only indirectly aiming at the eventual target cup, but there’s also less predictability because of the added, not perfectly flat surface. Factoring that in, the player has less control in where the ball goes because the ball could bounce weirdly off the table; there are weird dips in the wood on any table, and it’s just hard to know exactly how it will bounce. Even beyond that, though, it’s also just simply another variable, so even if the table’s surface were 100% flat, it would still add something to the list of things you have to perfect, in comparison to the single contact with your paddle made in a Rally Shot.

I’m sure there are other reasons, too, but whatever it is, I think it’s pretty clear: Don’t Doobie. We’re better at shooting than serving.

Now, just to be clear, this departure from the historical way of thinking doesn’t extend to the reverse situation – when your opponent has the Serve. Yes, you’d rather have your opponent Serving than actually shooting at the cup, but you’d also rather have your own shot. Catching a doobie to give your opponent back the Serve is still really hurting your team.

Where the discussion gets a bit trickier is in comparing teammates. It’s one thing for Nog to never catch his own doobies, because he’s so accurate in Live Play. But what happens if his teammate is perfectly average, and shoots the tournament means of 13.6% in Rally Shot Rate and 10.3% in Serve Rate? It would never make sense for Nog to catch the doobie to give to his teammate to Serve, but the numbers would argue it makes sense for his teammate to sacrifice his 13.6% Rally Shot for Nog’s 14.0% Serve Rate. If Nog were playing with a below average partner, it would be an even clearer case.

At least, that’s what the numbers say, but here I think we need to look beyond the stats. Pong, first and foremost, is a gentleman’s game, and that extends to believing in and supporting your teammate. Telling your partner that he should sacrifice his own shots to give to you doesn’t seem to me like a great way to inspire confidence in the brother you’re doing battle with.

And even beyond that, it’s just taking things way too far. Obviously, we love this game. We get competitive about it. I’m thousands of words into writing this, and you’re at the same point reading it. But suggesting that type of tactic is a little too cold blooded for my taste, and means we’re all taking this way too seriously. At its heart, pong is fun and inclusive. Let’s keep it that way.

395 Love.