On February 4, 19-year-old Timothy Piazza, a pledge of Penn State’s Beta Theta Pi fraternity, died after a night of drinking and being hazed. The particulars of this happening are certainly disconcerting, but this all became especially close to home when I learned that a graduate of my alma mater Niskayuna High School was involved, and is now being charged with Evidence Tampering in an attempt to cover up said particulars. This prompted a discussion about the affair among my high school friends, and the eventual posit of an even broader question:

On February 4, 19-year-old Timothy Piazza, a pledge of Penn State’s Beta Theta Pi fraternity, died after a night of drinking and being hazed. The particulars of this happening are certainly disconcerting, but this all became especially close to home when I learned that a graduate of my alma mater Niskayuna High School was involved, and is now being charged with Evidence Tampering in an attempt to cover up said particulars. This prompted a discussion about the affair among my high school friends, and the eventual posit of an even broader question:

How much longer do you think frats exist? I would bet they’re no longer at most reputable schools by the time our kids go to college.

Very hard to defend, ultimately.

As a former frat bro, this assertion stings my core. Not because of the first part, though, which is mostly a snap-judgement one might make from Mt. Pious (fuckin Princeton grads!) when you’re texting a chat group of your best friends. There are, in fact, many reasons why Greek life, from a practical standpoint, would be far more difficult to excise than you’d think:

As a former frat bro, this assertion stings my core. Not because of the first part, though, which is mostly a snap-judgement one might make from Mt. Pious (fuckin Princeton grads!) when you’re texting a chat group of your best friends. There are, in fact, many reasons why Greek life, from a practical standpoint, would be far more difficult to excise than you’d think:

- Fraternity men are some of the most generous donors to their alma maters

- One in eight students at four-year colleges lives in a Greek house, and the collective value of these buildings – many of which are owned by the Greek institutions themselves – is $3 billion. Replacing those facilities is cost-prohibitive.

- Traditional colleges compete not only among themselves, but now also with more economically-responsible alternatives (e.g., online degrees). A huge reason they continue to attract hundreds of thousands of students every year – even in the face of crippling loans – is that they market the experience as one hell of a good time. Fraternities go a long way in fostering that perception, as they essentially provide colleges with unlimited social programming.

- That programming falls outside of the school’s budget, and outside of any formal sanctioning by the school – removing potential liability that could threaten an administration.

- There are thorny legal barriers. Any ban would infringe on the Constitutional right to freedom of association, a defense which interest groups like FratPAC have been successfully citing since ya boy Elephalet Nott rubber-stamped this whole system in 1825.

In that light, it’s unlikely Greek life ends in these next few decades, but it was really more the belief that we should eliminate it that had me bitter. After all, I have infinitely fond memories of my own experience, and would live it all over again 395 times out 100. The fraternity, as an institution, is integral to my life and my identity.

In that light, it’s unlikely Greek life ends in these next few decades, but it was really more the belief that we should eliminate it that had me bitter. After all, I have infinitely fond memories of my own experience, and would live it all over again 395 times out 100. The fraternity, as an institution, is integral to my life and my identity.

There is, though, a fairly compelling case that the institution is a net detriment to society. I mean, whether it’s disturbingly-rapey emails from American U’s Epsilon Iota, or wildly racist chants from Oklahoma’s SAE, we’ve all heard tales of troubling fraternity behavior. Beyond the many one-off examples, though, there are broader trends that paint a problematic picture:

- Fraternity members are 300% more likely to commit rape

- Since 2005, 60+ people have died in incidents linked to fraternities

- 86% of fraternity men binge-drink, compared to 46% of non-fraternity men

- Fraternity house members were twice as likely to fall behind in academic work, engage in unplanned sex, or be injured after drinking

- Virtually every fraternity is less diverse than the college as a whole, counteracting positive steps that institutions have taken with respect to racial and socioeconomic diversity

This obviously doesn’t reflect well on the whole Greek system, but these data don’t result in an open and shut case, either. Many of those statistics cited above don’t prove any causation effect. In fact, it’d be quite plausible to argue there is merely an overlap, not a gateway; that people inclined toward malicious behavior also happen to be attracted to the good-intentioned-but-still-deviant lifestyle of fraternities. It’s a chicken-or-the-egg dynamic, if you will, and difficult to say for sure.

That is, at least until you remove the system and compare what happens, but that’s a complicated affair, too. Many theorize that working within the Greek system, a known quantity, is better than not having it at all, forcing the same behavior into off-campus houses or underground fraternities that can’t be regulated by colleges. “They’re still there, exhibiting the same behaviors, only now they don’t really have to answer to anybody,” the thinking goes.

That is, at least until you remove the system and compare what happens, but that’s a complicated affair, too. Many theorize that working within the Greek system, a known quantity, is better than not having it at all, forcing the same behavior into off-campus houses or underground fraternities that can’t be regulated by colleges. “They’re still there, exhibiting the same behaviors, only now they don’t really have to answer to anybody,” the thinking goes.

I can see that line of reasoning, but I’m not sure what’s fair to conclude. “The colleges that have abolished fraternities — mostly small private liberal arts colleges like Colby, Bowdoin, Middlebury, and Williams — say publicly that they do not regret the decision. While the bans at these colleges did lead to secret fraternities sprouting up off-campus, their influence has waned over the years.”

“Not regretting the decision” isn’t exactly the strongest endorsement I’ve ever heard, but most of the “Don’t Kill Frats” arguments seem to only point out why the move won’t help. They’re more, “there’s no good reason to get rid of them!,” rather than, “here’s why we need to keep them.” Honestly, in reflecting on my own thoughts and in researching this piece, there don’t seem to be all that many arguments for fraternities – for why they have any positive merit.

One common rationale is what exemplary men and women Greek alum become – that “when fraternities and sororities are done well, they really are extraordinary leadership opportunities.” According to that Gallup article, “college graduates who were members of fraternities or sororities are more likely to be engaged in work and thriving in all five elements of well-being compared with graduates who were not fraternity or sorority members.”

It is true, many pioneers of industry, political leaders, U.S. Presidents (including 5 DKEs!), etc. have a Greek background, but I’m a bit dubious of this hypothesis. This appears another chicken-and-the-egg situation, with any causation effect murky at best.

It is true, many pioneers of industry, political leaders, U.S. Presidents (including 5 DKEs!), etc. have a Greek background, but I’m a bit dubious of this hypothesis. This appears another chicken-and-the-egg situation, with any causation effect murky at best.

Pro-Greek arguments also usually point out the Philanthropic dynamics the system creates. According to the NAIC, last year alone saw fraternities volunteer a collective 3.8 million hours, and raise $20.3 million for various causes. I guarantee those numbers would go down, if not for those individuals being members of these Greek societies. But by how much? And isn’t $20M a small drop in America’s overall charity bucket? And aren’t there probably more effective ways of motivating undergrads to serve their communities?

In fact, now that I think about it…. why don’t top-tier institutions mandate a minimum number of community service hours? Doesn’t requiring students volunteer 10 hours a semester in order to graduate seem like a no-brainer?

Anyway, beyond those two explanations, the entirety of any remaining justification is boiled down to this line from The Atlantic:

When arguments are made in their favor, they are arguments in defense of a foundational experience for millions of American young men…. Many more thousands of American men count their fraternal experience—and the friendships made within it—as among the most valuable in their lives.

This, here, is the argument that personally resonates. Fraternities are incredibly effective at fostering life-long bonds, creating a pseudo-family out of those shared relationships and experiences. The term Brotherhood is not a mischaracterization at all. La Familia.

The reality, though, is that to continue creating that unique connection, some sort of hazing process is probably required. The trials you go through both create shared memories with your pledge brothers, going through them with you at the time, and connect you with past and future generations who went through the same things.

The reality, though, is that to continue creating that unique connection, some sort of hazing process is probably required. The trials you go through both create shared memories with your pledge brothers, going through them with you at the time, and connect you with past and future generations who went through the same things.

More so, though, hazing creates a substantial barrier to entry. You might let someone new into your group of friends. But into your family? They have to earn it, and that’s where hazing comes in. It’s unpleasant, takes dedication, and weeds out those who don’t want it. But it’s also where fraternities intrinsically become ethically complicated; hazing – even if it’s not the leading cause of fraternity-related injuries – is morally suspect, at best.

The Wall Street Journal lays it out nicely:

“When shameful or even tragic incidents occur—from displays of racial bigotry to sexual assault to deaths due to hazing or high-risk drinking—they happen because of the poor judgment of individual college students and the culture that individual chapters have allowed to continue. They are not a result of the Greek system itself or the influence of the fraternity’s national organization.”

The idea of banning all fraternities because of a few bad players seems far too blunt.”

Just because some people are idiots doesn’t mean a system is inherently bad. Why should the irresponsible ruin it for the rest of us?

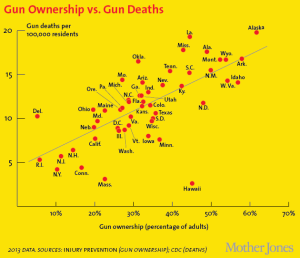

The reason? Guns. It’s literally the stance I argue for any time our right to bear arms comes up.

Yes, you might like guns. You might be licensed to carry one, and trained in how to use one. You might do so safely, in a way that never leads to any harm being done. And you might feel safer because you have one. On an individual level, you might actually be safer.

But you know who would be safer if you didn’t have a gun? This country, including you on a personal level if nobody else had one either. And isn’t that an admirable-enough result that you’d be willing to relinquish your ability to do so?

But you know who would be safer if you didn’t have a gun? This country, including you on a personal level if nobody else had one either. And isn’t that an admirable-enough result that you’d be willing to relinquish your ability to do so?

I look at fraternities in the same way. Yes, joining a fraternity gave me one of the best experiences I’ve ever had. It made me friends from the heart, forever. And yet, if eliminating that system would benefit us on a macro-level, I’d be all in favor. It would pain me, but I’d be willing to sacrifice.

I just don’t think we can conclude that. The cause and effect is not nearly clear enough. At least, not yet.

Until then: DKE Once, DKE Twice.