For a long time, I was pretty much against watching any serialized television show as the program was being released. Essentially, I would do my best to avoid watching any series that had yet to broadcast its ultimate finale. Unless the conclusion had already aired, no dice.

There were three real impetuses for this strategy, the first purely practical. College schedules invariably fluctuate week to week; you might have Tuesday free for one week, but then the next has you doing homework, and the week after that, partying. Unless you had DVR/TiVo – which I did not – you’d inevitably miss an episode or two, which would throw off the whole chronological sequence of the show, and then the series as a whole. Episodic programs like South Park, that rarely rely on you having seen the previous week’s installment, were my bread and butter because of this very reason.

There were three real impetuses for this strategy, the first purely practical. College schedules invariably fluctuate week to week; you might have Tuesday free for one week, but then the next has you doing homework, and the week after that, partying. Unless you had DVR/TiVo – which I did not – you’d inevitably miss an episode or two, which would throw off the whole chronological sequence of the show, and then the series as a whole. Episodic programs like South Park, that rarely rely on you having seen the previous week’s installment, were my bread and butter because of this very reason.

The second reason is that cliff hangers can be excruciating, and waiting a whole week in between episodes, or nine months in between seasons, is pretty brutal. I deemed it better to binge-watch the entire series after it had all come out. I could watch the show until I needed a break, or it ended. Of course, the show might end with me wanting more, but at a certain point that’s unavoidable, and this seemed to be the best way to avoid having an unquenched craving for any given program.

The third reason revolves around proven quality. If you’re about to dive into a 6 or 7 season drama, you’re going to invest a whole lot of your time in hopes that it pays off. Nobody wants to grind through two and a half seasons hoping things pick up, only to either quit out of frustration or push through til the end and find out it was a huge waste of time.

The Wire, for example, is comprised of 60 one-hour-or-so-long episodes that span five seasons. That’s two and a half straight days of content. I can’t fathom anybody watching it like that, but a more realistic, yet still daunting, approach would be two episodes per day. That’s still an entire month of your time. It’d much safer to watch The Wire for the first time in 2013 than it was in 2002 as it was initially airing, because we have hindsight to tell us that it’s often regarded as the greatest show of all time. If you’ve yet to watch that series, you can feel confident doing so now, because you’ve been reassured by your friends and the internet that the show is a canonical behemoth. There’s almost no risk – you know it will pay off. The series Lost, on the other hand, had a reputedly exhilarating beginning, but a notoriously underwhelming finale. Hindsight allows us to avoid mucking it up with series like this.

The Wire, for example, is comprised of 60 one-hour-or-so-long episodes that span five seasons. That’s two and a half straight days of content. I can’t fathom anybody watching it like that, but a more realistic, yet still daunting, approach would be two episodes per day. That’s still an entire month of your time. It’d much safer to watch The Wire for the first time in 2013 than it was in 2002 as it was initially airing, because we have hindsight to tell us that it’s often regarded as the greatest show of all time. If you’ve yet to watch that series, you can feel confident doing so now, because you’ve been reassured by your friends and the internet that the show is a canonical behemoth. There’s almost no risk – you know it will pay off. The series Lost, on the other hand, had a reputedly exhilarating beginning, but a notoriously underwhelming finale. Hindsight allows us to avoid mucking it up with series like this.

I still find myself swayed by this last consideration, but the other two I now find much less compelling. I now have TiVo and On-Demand, so the practical issue of staying on top of missed episodes is completely moot.

My preference has also shifted away from binge-watching, and much of this is due to my delight in analyzing these shows. “How did you feel about that plot event?” “What do you think is going to happen next with the character?” I love this sort of commentary or questioning, but these inquires become nullified when binge-watching; not only is it awkward to predict future occurrences when others know the truth of said future, the discussion of what just happened, and the conjecture regarding what will happen, get swept away by the urge to hit “Play Next,” as it’s is too tempting to succumb if you have that option.

Further adding to this is that – spoiler alert – the internet will often ruin plot twists for you no matter how hard you try to avoid them. Even if this weren’t a threat – that you could filter out any such content – I still think I’d want to watch a show as it airs because I actively seek out that type of spoiler-riddled content. Sites like Grantland.com generate close readings of every episode, and I take great pleasure in reading those reactions, as they teach me things I didn’t know (e.g. who knew Walter White incorporates into his own behavior idiosyncrasies or objects from other Breaking Bad characters he comes across?) and provide a fresh perspective. If I tried to wait until after the series finale to dive into the pilot, I’d miss out on all those alternative and informative insights. It would dampen my experience and my understanding of the shows that I love.

Further adding to this is that – spoiler alert – the internet will often ruin plot twists for you no matter how hard you try to avoid them. Even if this weren’t a threat – that you could filter out any such content – I still think I’d want to watch a show as it airs because I actively seek out that type of spoiler-riddled content. Sites like Grantland.com generate close readings of every episode, and I take great pleasure in reading those reactions, as they teach me things I didn’t know (e.g. who knew Walter White incorporates into his own behavior idiosyncrasies or objects from other Breaking Bad characters he comes across?) and provide a fresh perspective. If I tried to wait until after the series finale to dive into the pilot, I’d miss out on all those alternative and informative insights. It would dampen my experience and my understanding of the shows that I love.

This is an idea on which I dwell.

In 1973, a literary critic and Yale professor named Harold Bloom published a book called The Anxiety of Influence, after which this BlogCat is titled. In this text, Bloom discusses the relationship between poets and their predecessors, and posits that a “poet is condemned to learn his profoundest yearnings through an awareness of other selves. The poem is within him, yet he experiences the shame and splendor of being found by poems – great poems – outside him…. Poetic Influence always proceeds by a misreading of the prior poet, an act of creative correction that is actually a necessarily a misinterpretation.”

In 1973, a literary critic and Yale professor named Harold Bloom published a book called The Anxiety of Influence, after which this BlogCat is titled. In this text, Bloom discusses the relationship between poets and their predecessors, and posits that a “poet is condemned to learn his profoundest yearnings through an awareness of other selves. The poem is within him, yet he experiences the shame and splendor of being found by poems – great poems – outside him…. Poetic Influence always proceeds by a misreading of the prior poet, an act of creative correction that is actually a necessarily a misinterpretation.”

This is an extremely esoteric literary argument that I’m willing to admit is difficult to grasp. However, the gist of it is that poets must deal with the anxiety surrounding this issue, namely that to be considered great, one must have an original voice, yet finding that original voice is reliant upon being influenced by those that have come before. That’s quite the paradox. I’d be a bit out of my depth if I tried to comment on or further explain Bloom’s theory. However, I can certainly assert that I find I face a similar anxiety when trying to consider and evaluate a television series in the context of the critical whirlwind that spins around it.

Immediately after watching an episode, one typically has a certain reaction to said episode. It could be, “Ehh, that wasn’t as good as last week’s. And that one wasn’t even good. Why am I even watching this garbage?” It could be, “Holy fuck! I can’t believe that just happened! That was freaking amazing!” And, of course, it could be somewhere in between.

I inevitably have this sort of organic, uncut take on the content I just watched, and yet things often change completely when I read online recaps the next day. If I think the latest episode was underwhelming, for example, I might read a review that saw it in a much more positive light, which causes me to reconsider my stance. Things are pointed out that I did not previously pick up on. Events or characters are thought about in a different way. Details I’d forgotten about are recounted, resulting in everything making a lot more sense, or having a deeper meaning.

Not all these new ideas are accepted, of course. Just because several Game of Thrones critics thought Jon Snow and Ygritte’s virginity-burgling tryst in the ice cave was enthralling and romantic doesn’t mean I’ll stop thinking it was completely ludicrous and heavy-handed. But some valid points do hit home, and it really causes problems in determining my thoughts about the quality of a show.

Not all these new ideas are accepted, of course. Just because several Game of Thrones critics thought Jon Snow and Ygritte’s virginity-burgling tryst in the ice cave was enthralling and romantic doesn’t mean I’ll stop thinking it was completely ludicrous and heavy-handed. But some valid points do hit home, and it really causes problems in determining my thoughts about the quality of a show.

I might watch an episode and on my own rate it a C+. But what if I read three critiques of that episode that point out things that I missed, and now feel like it’s an A-? Isn’t that sort of a problem that the show didn’t make me realize those things on my own? On the other hand, clearly other people noticed due to only the show itself, so is quality somehow dependent on my subjective perceptive capacity?

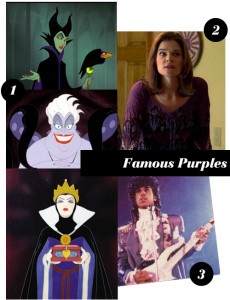

For instance, I watched the first 5 seasons of Breaking Bad without it registering that Marie Schrader was constantly wearing purple (hard to believe in hind sight, I know). It’s only a small detail, but as I began to read commentary of the series in preparation for the its final 8 episodes, people kept pointing out this fashion trend, and it increased my appreciation for the series. But the show on its own, self-contained, didn’t do that to me. It was the commentary that I read. Yet the purple attire was contained within the show – those close readings didn’t just make it up. But then again, I’d never have known about it if all I did was watch the show itself.

For instance, I watched the first 5 seasons of Breaking Bad without it registering that Marie Schrader was constantly wearing purple (hard to believe in hind sight, I know). It’s only a small detail, but as I began to read commentary of the series in preparation for the its final 8 episodes, people kept pointing out this fashion trend, and it increased my appreciation for the series. But the show on its own, self-contained, didn’t do that to me. It was the commentary that I read. Yet the purple attire was contained within the show – those close readings didn’t just make it up. But then again, I’d never have known about it if all I did was watch the show itself.

And now I’m spiraling down a rabbit hole.

Essentially, my opinion of a show, an episode, a series, or really any other text, is not determined solely by factors internal to the text itself. It’s also influenced by the external commentary around it, which itself draws from the text’s internal constitution.

I’m just not sure how to feel about that.

……………………………..

Also, I couldn’t work these two things into the post organically, so to conclude, here’s your obligatory 395 reference, and if you’re a Breaking Bad fan, check out this picture below. It’s hysterical:

The reader’s response, especially in regard to poetry, is almost always a misinterpretation no matter how much it is steeped in reason. As you noted, the poet who seeks to find his voice must first grasp the meanings within the verses written by great poets before him. This is an entirely daunting task when we don’t have access to the original poets themselves. Bill Shakes and T.S. Eliot won’t be at next years Comic-Con to preview their upcoming collections and divulge secrets about their writing process. Fortunately, we have precisely that when it comes to contemporary TV and Movies. Today we can hear Vince Gilligan tell us exactly what was going on in a certain episode of Breaking Bad, or we can listen to David Simon explain the implied back-story of a character in The Wire. In short, we are constantly being influenced by external aspects of texts, or any art, from those in the audience and the creators themselves. This has probably always been the case, though now we live in a world where everybody can be a critic and widely disseminate their opinion. Perhaps this is a trope within our highly social [media] culture.

BTW, way to bring it back to Cefalu’s class haha.

This seems germane: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_of_the_Author

I like the idea that comprehension of a text isn’t necessary for consumption of art since it accounts so literally for misreadings. For example you can physically read a book without understanding any of what’s written. Obviously that’s not what you want to happen when you read or watch something, but I like how well it fits into the “death of the author” theory. Its very helpful concept in fine art where the majority of the work you deal with is so opaque that understanding authorial intentions isn’t really an option.

Its interesting to consider this in light of our highly social [media] culture. Basically anyone who cares to has access to a close reading of any piece of media available. We can all get reasonably close to what an author’s intentions are, and learn about their milieu and history. In a sense this takes all of the guesswork out and leaves attentive viewers at a point where they can react purely to their encounter with a work of art.