“This was going to be my last,” Pike Bishop murmurs into his whiskey after a botched robbery of a railroad office results in the decimation of his gang. “I’d like to make one good score and back off.” His partner, Dutch, his voice dripping with venom, snaps “Back off to what?” The question hangs ominously in the air as the two friends stare silently off into space, knowing that there is no answer.

Before long, both Pike and Dutch (played, respectively, by William Holden and Ernest Borgnine) will be among the pile of dead bodies that result from the orgiastic climax of Sam Peckinpah’s infamous Western classic, The Wild Bunch (1969). By one estimate, the body count of the climactic fight is 112 in about 5 minutes of screen time (with the grand total for the entire movie standing at 145). It is beautifully shot and shockingly violent.

The bulk of the critical attention on Peckinpah’s career has focused, unsurprisingly, on exactly this element of his movies. There is a reason that Monty Python’s take on “Bloody Sam” involves a piano fallboard severing John Cleese’s hands while Graham Chapman is impaled through the stomach by a keyboard.

And there really is a lot to say about his hyper-stylized violence! Peckinpah was a major point of inspiration for people like Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese (who famously described The Wild Bunch as “savage poetry”). His influence on the past few decades of action movies is immense. However, an element of his movies that I rarely see discussed is the underlying ideology with which Peckinpah approached his art.

He was one of the first mainstream, commercial American directors to really start putting into practice some of the technical lessons absorbed from the Italian, French, and Japanese New Wave movements (e.g. intercutting shots of the same action from multiple angles, mixing of slow motion and sped up action within the same sequence, and other ways of playing with visual continuity). His favorite filmmakers were people like Akira Kurosawa, Alan Resnais, René Clément, and Federico Fellini.

What set Peckinpah apart from many of his influences is the way he used this New Wave aesthetic sensibility in service of the depiction of senseless, over-the-top violence. Not to say that some of his inspirations didn’t have their share of violence (Kurosawa in particular), but no other director before him treated that violence with the same sensuousness and awe or more fully realized the way the technological innovations of the film medium could be used in order to exploit this violence.

More so than just the technical developments, there is an important ideological through-line from Peckinpah to his New Wave forebears. This is no more evident than in the works of Jean-Luc Godard, despite the seeming gulf between the Peckinpah’s fixation on constrained masculinity exploding into ultraviolent catharsis and Godard’s pre-occupation with the daily lives of effete Paris intellectuals. Both directors focus on characters that have no future.

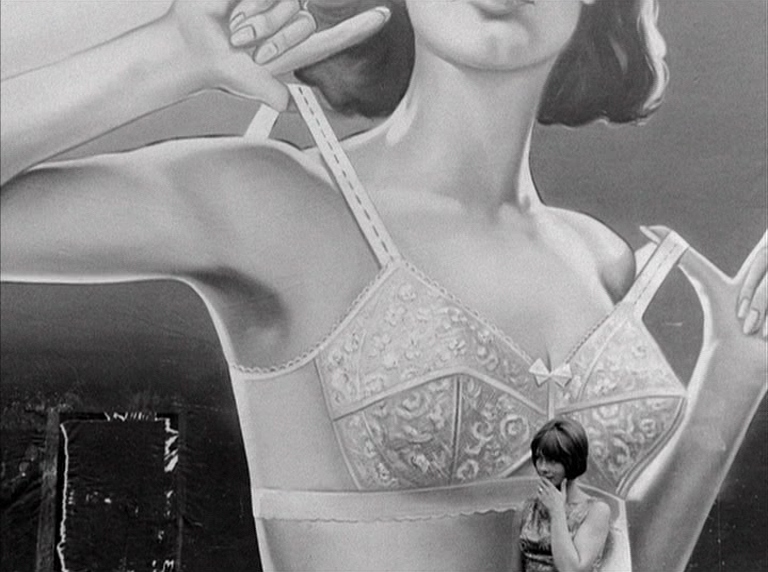

In the case of Godard, his characters are worldly and even occasionally revolutionary, but also flâneurs: they have no careers and no plans for the future, preferring instead to languish in flights of fantasy. Like Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless (1960) taking on the affectations of Humphrey Bogart, Godard’s characters want to live a life like those portrayed in the movies and popular culture they consume, precisely because their reality in and of itself is so alienating that they cannot bear to confront it directly. Instead of forming real personal connections or rich inner lives, they fetishize these symbols of commercial appeal as a substitute for identity. The corruptive appeal of the commodification of daily life prevents them from living fulfilling lives, and more often than not ends in tragedy.

Peckinpah, on the other hand, rarely focused his movies on the young. Instead, his movies almost exclusively focus on the old. These are people that have no future because they have been rendered irrelevant by the relentless march of civilization. The answer to Dutch’s question (“Back off to what?”) is, simply, oblivion. There is no more room for them in the new world order. These are the people swept aside to make way for the modern world that Godard’s youth are fetishizing. It is the other side of the same Marxist coin.

To be fair, the Western (which Peckinpah explored on in one way or another for most of his career) is probably the most Marxist of American literary genres, even if John Wayne wouldn’t want to admit it. After all, the entire philosophical underpinning of the genre is about the twilight of the freedom of the frontier and the inevitability of civilization (represented always by railroads, industry, and business; i.e. capitalism) in absorbing and co-opting that freedom.

The most unique of Peckinpah’s treatments is probably in 1973’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, one of the most idiosyncratic Westerns ever made. The film is a lyrical retelling of one of the foundational myths of the Old West: an aging gunslinger named Pat Garrett (played by the great James Coburn) is sent to take down his former partner-in-crime (the infamous outlaw Billy the Kid – played by Kris Kristofferson).

.jpg?bwg=1547295453)

What makes this film so unusual is the tone, reinforced by the haunting Bob Dylan soundtrack (most famously “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”, which plays over the scene above). It is a slow, elegiac meditation on violent acts that nobody involved feels particularly interested in committing but feel forced to do so out of some vague sense of necessity. The specter of capitalism imposing its “civilized” order onto the Old West is regarded with a sense of almost existential dread and inevitability that borders on the Lovecraftian.

The great moral failing of Pat Garrett in the eyes of the other characters in the film is not that he is out to commit murder, nor that he is betraying an old comrade. In fact, both of those acts in and of themselves are normalized. Instead, the great sin is specifically that he is committing them not out of revenge or honor or fortune, but on the behest of a group of rich politicians, cattle barons, and land speculators. He is, in essence, a class traitor. In fact, he too thinks of himself as a traitor, and prevaricates and procrastinates throughout the movie with distractions to avoid having to face the reality of his awful task.

Why does he do it? Why does he not quit? Because he was voted the Sheriff of Lincoln County and is ostensibly carrying out the will of the “electorate”. However, it’s not really the electorate (who remain largely invisible as anything but hapless bystanders to the violence throughout the film) that he works for, as is made clear when he visits the cigar-smoking, tuxedo-wearing patricians that give him his marching orders. The idealism of democracy has been subverted by the cynicism of capitalism for the purpose of exacting state-sanctioned violence on those deemed meddlesome to the business interests of the rich elite (based on the historical Santa Fe Ring).

The other characters in the movie serving as instruments of the law (e.g. “Alamosa” Bill) are no more honorable than the criminals they are deputized to destroy; the actual beneficiaries of the new “law and order” don’t have to get their hands dirty since they can always bribe or blackmail those below them in the social hierarchy to do their bidding. When “Alamosa” Bill is killed at the hands of Billy the Kid, his last words are “At least I’ll be remembered.” Becoming part of the legend of the last great outlaw is the only way that history will remember him.

This idea is visited again in the follow-up to The Wild Bunch, 1970’s The Ballad of Cable Hogue, in which Jason Robards’ title character tries to get rich by profiting off of a water source in the desert. He succeeds in becoming profitable, but is too hopelessly out of touch with what it means to be rich that he lives the same backwater lifestyle in nicer clothes. In the end, his inability to keep up with the changing world results in his death when he is run over by an early automobile. He is immortalized only in the legend of his finding water in the desert, as the land is sold off to the same railroad that spurned his business offer early in the movie.

.jpg?bwg=1547461766)

In fact, a deep sense of history and its victims was a motivating factor for Peckinpah. The Wild Bunch and the decline of the mythic West he explicitly intended as a parallel for 1960s America, and what he saw as the normalization of shocking violence as a result of the Vietnam War (and the Cold War more broadly). He saw the US as on the precipice of social and economic upheaval just as profound as that of the 1880s, which saw the death of the romantic Old West of legend and its replacement with the capitalist excess of the Gilded Age.

It’s a theme that would obsess him as he moved beyond the Western genre as well, for example in the villainous depiction of the CIA in both 1975’s The Killer Elite and 1983’s The Osterman Weekend. Even Convoy (1978), an otherwise goofy trucker-sploitation movie starring Kris Kristofferson, slips into its second act a surprisingly nuanced discussion on revolutionary praxis. The protagonists’ spontaneous act of rebellion becomes recontextualized by the press as a principled political/revolutionary movement, whose goals are quickly co-opted by the state governor to serve as a soundbite for his re-election campaign, while the protagonist has to decide whether or not to work within existing power structures to exert positive change.

At the end of the movie, the governor’s eulogy, glorifying truckers as “the living embodiment of the American cowboy tradition,” is presented at first as a sincere reflection on the senselessness of the violence that was used to destroy the apparent revolution, then slyly undermined when Peckinpah cuts to reveal that the governor is reading his heartfelt message from cue cards. Even the emotional denouement is cynically repurposed to further the needs of the rich and powerful.

In no movie does Peckinpah take it so far, though, as in Cross of Iron (1975). The movie is set on the Eastern Front of World War II as the Wehrmacht, the glittering symbol of Nazi Germany’s military might, is crumbling beneath the onslaught of the Red Army. The greatest enemy faced by the German soldiers, however, is not Russian wrath, nor is it the fanatical Nazi Party represented by Leutnant Triebig; it is the Prussian aristocrat Hauptmann Stransky (played by Maximilian Schell, and the prototype for Inglorious Basterds’ iconic Hans Landa). He represents an ancient class of privilege and standing that predates the war and, as is stated several times during the movie, will outlast it. No matter what happens during the war, Stransky (and what he represents) will endure as an obstacle to the livelihood of the common man. Even World War II and all its horrors is a mere footnote in the endless class struggle of history.

As Peckinpah said, “When you’re dealing in millions, you’re dealing with people at their meanest. Christ, a showdown in the old West is nothing that compares with the infighting that goes on over money.”